Greetings to all from Liturgy Brisbane.

On 8 December last year, the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception marked the 150th anniversary of the proclamation of Saint Joseph as Patron of the Universal Church. Pope Francis chose this occasion to declare a Year of St Joseph for the entire Church running from December 8, 2020 to December 8, 2021.

The Pope's apostolic letter, Patris corde (With a Father’s Heart), is presented in this issue of LITed.

Pope Francis states that he was particularly moved to write about St. Joseph “during these months of pandemic, when we experienced, amid the crisis, how “our lives are woven together and sustained by ordinary people, people often overlooked…

Each of us can discover in Joseph – the person who goes unnoticed, a daily, discreet and hidden presence – an intercessor, a support and a guide in times of trouble. ”

The second article in this issue highlights the ways in which St Joseph is celebrated in the liturgy.

The third article explores references to St Joseph in the Scriptures and the conclusions that can be drawn about him from the biblical narrative.

A reflection on the various aspects of St Joseph's life and character will be published on the website of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference each month throughout 2021. Each reflection can be shared and reproduced provided that appropriate attribution is given to the author of the reflection.

The January reflection by Archbishop Mark Coleridge and the February reflection by Michelle A. Connolly R.S.J. are included below.

With very best wishes from all of us at Liturgy Brisbane.

On 8 December last year, the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception marked the 150th anniversary of the proclamation of Saint Joseph as Patron of the Universal Church. Pope Francis chose this occasion to declare a Year of St Joseph for the entire Church running from December 8, 2020 to December 8, 2021.

The Pope's apostolic letter, Patris corde (With a Father’s Heart), is presented in this issue of LITed.

Pope Francis states that he was particularly moved to write about St. Joseph “during these months of pandemic, when we experienced, amid the crisis, how “our lives are woven together and sustained by ordinary people, people often overlooked…

Each of us can discover in Joseph – the person who goes unnoticed, a daily, discreet and hidden presence – an intercessor, a support and a guide in times of trouble. ”

The second article in this issue highlights the ways in which St Joseph is celebrated in the liturgy.

The third article explores references to St Joseph in the Scriptures and the conclusions that can be drawn about him from the biblical narrative.

A reflection on the various aspects of St Joseph's life and character will be published on the website of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference each month throughout 2021. Each reflection can be shared and reproduced provided that appropriate attribution is given to the author of the reflection.

The January reflection by Archbishop Mark Coleridge and the February reflection by Michelle A. Connolly R.S.J. are included below.

With very best wishes from all of us at Liturgy Brisbane.

Articles on Saint Joseph

Patris corde (With a Father's Heart)In his Apostolic Letter, Pope Francis describes Saint Joseph as a father who is tender and loving, obedient, accepting, creatively courageous, selfless and industrious .

|

Celebrating St Joseph in the LiturgyThis article by Tom Elich explores the liturgical days which commemorate St Joseph and sets out some practical suggestions for celebrating the Year of St Joseph in schools and parishes.

|

St Joseph in ScriptureThe website of the Oblates of St Joseph in the United States contains a wealth of information on St Joseph in scripture and liturgy. Some key points of interest are highlighted.

|

YEAR OF SAINT JOSEPH - REFLECTION

January 2021

The Gospels of Matthew and Luke both have genealogies of Jesus Christ. They are not identical, in part because each seeks to make a different theological point. Each in its different way traces the lineage of Joseph.

The reasons for this are more Christological than biological. The fundamental promise of the Old Testament is the promise to Abraham and his descendants – a promise of life bigger than death, symbolised by offspring and patrimonial land, which were the symbols of life beyond death in the cultures that produced the Bible.

The question through time was: How is this blessing to be mediated in the life of the People of God? Different answers were given at different times. The God-given institutions were seen as mediating the Abrahamic blessing – the monarchy, the prophetic movement, the priesthood – depending upon which was in the ascendant at any given time. Ancient Israel begins as a loose tribal federation with no centralised government. That changes once Israel faces the new kind of military threat represented by the Philistines. They were a formidable foe, culturally more advanced and with the latest in high-tech weaponry; and they seemed to have the tribes of Israel surrounded. The new peril demanded a new kind of military and political unity; and that’s when you first hear in the Bible the cry for a king.

The decision to have an anointed king, a Messiah, came at the end of a slow and painful process, as we see in 1 Samuel 8-12. The theological problem was that God was supposed to be the only king of Israel; and any king on earth would seem to rival or reject the kingship of God.

A compromise was eventually reached to satisfy everyone militarily, politically and theologically. There would be a king – but a different kind of king. He would be as much subject to God’s law as anyone else in the community. Unlike the rulers of Egypt or Mesopotamia, he would be one of his brothers and sisters, like them a slave set free.

The reasons for this are more Christological than biological. The fundamental promise of the Old Testament is the promise to Abraham and his descendants – a promise of life bigger than death, symbolised by offspring and patrimonial land, which were the symbols of life beyond death in the cultures that produced the Bible.

The question through time was: How is this blessing to be mediated in the life of the People of God? Different answers were given at different times. The God-given institutions were seen as mediating the Abrahamic blessing – the monarchy, the prophetic movement, the priesthood – depending upon which was in the ascendant at any given time. Ancient Israel begins as a loose tribal federation with no centralised government. That changes once Israel faces the new kind of military threat represented by the Philistines. They were a formidable foe, culturally more advanced and with the latest in high-tech weaponry; and they seemed to have the tribes of Israel surrounded. The new peril demanded a new kind of military and political unity; and that’s when you first hear in the Bible the cry for a king.

The decision to have an anointed king, a Messiah, came at the end of a slow and painful process, as we see in 1 Samuel 8-12. The theological problem was that God was supposed to be the only king of Israel; and any king on earth would seem to rival or reject the kingship of God.

A compromise was eventually reached to satisfy everyone militarily, politically and theologically. There would be a king – but a different kind of king. He would be as much subject to God’s law as anyone else in the community. Unlike the rulers of Egypt or Mesopotamia, he would be one of his brothers and sisters, like them a slave set free.

The first king, Saul, was deposed by the prophet Samuel because he had disobeyed God. He was succeeded by David, chosen by Samuel at a young age. David came to the throne in about 1000 BC and reigned for something like 40 years. It was a time when, unusually, both the Egyptian and Mesopotamian empires were weak at the same time. Usually one was strong and the other weak, with the strong becoming the dominant power in the region.

David took advantage of the situation to carve out a mini-empire. His military success was seen as a potent sign of God’s blessing upon him and the people, as was his success in uniting the 12 tribes in a single kingdom with its united capital in Jerusalem. Eventually there came through the prophet Nathan a divine promise that the House of David would last forever. In other words, the Abrahamic blessing would be mediated eternally through the Davidic dynasty. This was fine until the Babylonian Exile in 587 BC, when the Davidic dynasty disappeared into the black hole of history because – the prophets said – the kings had disobeyed God’s law.

What then of God’s promise of an eternal dynasty? Was God perhaps powerless or unreliable? In order to save their faith in God’s absolute fidelity to the promise, ancient Israel gave the promise to David and his descendants an eschatological twist. In the End-Time, they said, an ideal Davidic king, a Messiah, would appear to usher in the reign of God. He would finally mediate to the People of God the fullness of the blessing promised to Abraham and his descendants. This is what Judaism meant when it said that the Messiah would come from the House of David.

Christianity came to see in Jesus crucified and risen the ideal Davidic king mediating a life bigger than death, most especially through his resurrection from the dead. He was the long-awaited Messiah, mediating the fullness of God’s blessing as priest, prophet and king.

The Gospels, therefore, are keen to stress Jesus’ connection to David in order to make that point. They recognise that Joseph wasn’t the biological father of Jesus, which is why in later tradition Davidic descent was often attributed to Mary as well as Joseph.

The New Testament says nothing of this – though it’s not impossible, given the custom of bridegrooms choosing a bride from within their own tribe. But again the point is less biological than Christological. It is more about who Jesus is than who Joseph is, more about what God does through Jesus than what God does through Joseph. It is often said that Mariology is a form of Christology, and the same is true of Josephology.

Mark Coleridge is the Archbishop of Brisbane and president of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference.

David took advantage of the situation to carve out a mini-empire. His military success was seen as a potent sign of God’s blessing upon him and the people, as was his success in uniting the 12 tribes in a single kingdom with its united capital in Jerusalem. Eventually there came through the prophet Nathan a divine promise that the House of David would last forever. In other words, the Abrahamic blessing would be mediated eternally through the Davidic dynasty. This was fine until the Babylonian Exile in 587 BC, when the Davidic dynasty disappeared into the black hole of history because – the prophets said – the kings had disobeyed God’s law.

What then of God’s promise of an eternal dynasty? Was God perhaps powerless or unreliable? In order to save their faith in God’s absolute fidelity to the promise, ancient Israel gave the promise to David and his descendants an eschatological twist. In the End-Time, they said, an ideal Davidic king, a Messiah, would appear to usher in the reign of God. He would finally mediate to the People of God the fullness of the blessing promised to Abraham and his descendants. This is what Judaism meant when it said that the Messiah would come from the House of David.

Christianity came to see in Jesus crucified and risen the ideal Davidic king mediating a life bigger than death, most especially through his resurrection from the dead. He was the long-awaited Messiah, mediating the fullness of God’s blessing as priest, prophet and king.

The Gospels, therefore, are keen to stress Jesus’ connection to David in order to make that point. They recognise that Joseph wasn’t the biological father of Jesus, which is why in later tradition Davidic descent was often attributed to Mary as well as Joseph.

The New Testament says nothing of this – though it’s not impossible, given the custom of bridegrooms choosing a bride from within their own tribe. But again the point is less biological than Christological. It is more about who Jesus is than who Joseph is, more about what God does through Jesus than what God does through Joseph. It is often said that Mariology is a form of Christology, and the same is true of Josephology.

Mark Coleridge is the Archbishop of Brisbane and president of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference.

| year_of_st_joseph_reflection_jan_2021.pdf | |

| File Size: | 221 kb |

| File Type: | |

YEAR OF SAINT JOSEPH - REFLECTION

February 2021

St Joseph, Attentive to the Word

“When the time came for their purification according to the law of Moses, they brought him up to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord.” Luke 2:22

Luke 2:22 shows that Joseph and Mary saw to it that, in every possible way, Jesus’ birth and early life were conducted according to the will of God. The Gospel of Luke focuses more strongly on Mary, the mother of Jesus, than on her betrothed husband,

Joseph. Nevertheless, by the time we hear this verse, early in the Gospel, we have learned some important facts about Joseph.

First, Joseph, who was betrothed to Mary, a virgin, was of the house and family of David (see Lk 1:27; 2:4). This means that Joseph traced his family tree back to the divinely chosen, anointed king of Israel: David. As an anointed king, David was, in the Hebrew language, a “messiah”. As a result, any son of Joseph would be counted not only as a descendant of David, but potentially a messiah.

However, six centuries before the time of Jesus, David’s messianic line had been exterminated. Since that time, the people of Israel had been waiting for God to provide them with another messiah who would bring a new time of great peace (see Isa 11:1-18). For this reason, Luke and the three other Gospels work very hard to show that Jesus is a legitimate son of David and thus the long-awaited messiah.

Second, Luke does not explain as the Gospel of Matthew does (see Matt 1:18-25) why Joseph decides to stay with Mary, who is pregnant before they are formally married. He simply states that Joseph went to Bethlehem to be registered in a census, going “with Mary to whom he was engaged and who was expecting a child” (Lk 2:5). A few verses later (Lk 2:16), we are told that the shepherds found Joseph with Mary following the birth of Jesus. Culturally, a child was honourable when it was recognised and named by the father. Joseph, who Luke says was thought to be the baby’s father (see Luke 3:23), allows the child to be named “Jesus” (Lk 2:21) as the angel who appeared to Mary had instructed (Lk 1:31).

All these actions by Joseph show that he is a man of his word who has remained with the woman to whom he is engaged, despite a pregnancy for which he is not responsible. More than that, he has seen that woman through childbirth in hard circumstances and has given her and her son a respectable identity in the world.

All these small pieces of information, when put into the larger, divine scheme of events that Luke offers us, also suggest that Joseph is a man with a distinct role in God’s desire to restore the world to right relationship with Godself. Joseph’s descent from King David, the anointed one, makes it possible for Jesus, despite his humble birth, to be truly the long-awaited Messiah of the Jewish people. While he does not know the full picture, by choosing generously and courageously to accept Mary as his betrothed in difficult circumstances, Joseph enables God’s will to be fulfilled.

More than this, Luke 2:22 indicates that Joseph is, in fact, a devout Jewish man who intentionally lives by God’s word. The verse states that Joseph and Mary deliberately made an arduous journey to Jerusalem to complete the requirements of the law of Moses for a new-born son.

“When the time came for their purification according to the law of Moses, they brought him up to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord.” Luke 2:22

Luke 2:22 shows that Joseph and Mary saw to it that, in every possible way, Jesus’ birth and early life were conducted according to the will of God. The Gospel of Luke focuses more strongly on Mary, the mother of Jesus, than on her betrothed husband,

Joseph. Nevertheless, by the time we hear this verse, early in the Gospel, we have learned some important facts about Joseph.

First, Joseph, who was betrothed to Mary, a virgin, was of the house and family of David (see Lk 1:27; 2:4). This means that Joseph traced his family tree back to the divinely chosen, anointed king of Israel: David. As an anointed king, David was, in the Hebrew language, a “messiah”. As a result, any son of Joseph would be counted not only as a descendant of David, but potentially a messiah.

However, six centuries before the time of Jesus, David’s messianic line had been exterminated. Since that time, the people of Israel had been waiting for God to provide them with another messiah who would bring a new time of great peace (see Isa 11:1-18). For this reason, Luke and the three other Gospels work very hard to show that Jesus is a legitimate son of David and thus the long-awaited messiah.

Second, Luke does not explain as the Gospel of Matthew does (see Matt 1:18-25) why Joseph decides to stay with Mary, who is pregnant before they are formally married. He simply states that Joseph went to Bethlehem to be registered in a census, going “with Mary to whom he was engaged and who was expecting a child” (Lk 2:5). A few verses later (Lk 2:16), we are told that the shepherds found Joseph with Mary following the birth of Jesus. Culturally, a child was honourable when it was recognised and named by the father. Joseph, who Luke says was thought to be the baby’s father (see Luke 3:23), allows the child to be named “Jesus” (Lk 2:21) as the angel who appeared to Mary had instructed (Lk 1:31).

All these actions by Joseph show that he is a man of his word who has remained with the woman to whom he is engaged, despite a pregnancy for which he is not responsible. More than that, he has seen that woman through childbirth in hard circumstances and has given her and her son a respectable identity in the world.

All these small pieces of information, when put into the larger, divine scheme of events that Luke offers us, also suggest that Joseph is a man with a distinct role in God’s desire to restore the world to right relationship with Godself. Joseph’s descent from King David, the anointed one, makes it possible for Jesus, despite his humble birth, to be truly the long-awaited Messiah of the Jewish people. While he does not know the full picture, by choosing generously and courageously to accept Mary as his betrothed in difficult circumstances, Joseph enables God’s will to be fulfilled.

More than this, Luke 2:22 indicates that Joseph is, in fact, a devout Jewish man who intentionally lives by God’s word. The verse states that Joseph and Mary deliberately made an arduous journey to Jerusalem to complete the requirements of the law of Moses for a new-born son.

To understand this verse we need to do two things. First, we need to read it in context, as part of a long sentence that goes to the end of v. 24. Second, to receive the rich meaning of these verses we need to be aware of Old Testament texts, the Word of God, that are referred to in Luke 2:22-24.

First, then, although the sentence of verses 22-24 begins and ends talking about the religious purification of a mother after giving birth as required by the Jewish law (see Lev 12:6), the main statement of the sentence is that Joseph and Mary brought Jesus to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord, according to a particular law of the Lord (Exod 13:2, 12, 13), which is quoted for us in the middle of the sentence. There are also other Old Testament texts that may be echoed in this presentation of Jesus to the Lord, especially the story of Hannah presenting her son Samuel to the Lord in 1 Sam 1:24-28 (but see also Exod 22:29; Neh 10:35-36).

Thus, Joseph and Mary perform two religious acts when they take Jesus to Jerusalem: they present Jesus to the Lord and they also offer a sacrifice for the purification of the mother of Jesus. Both of these acts are based in the Word of God. In fact, in the course of verses 22- 24, Luke refers three times to God’s Word, calling it “the law of Moses,” and twice “the law of the Lord.” Clearly, Joseph is presented as responding most attentively to the Word of God as expressed in the Scriptures.

The most important result of Mary and Joseph’s actions is that, from his very birth and introduction into the world, Jesus is fully righteous according to God’s Word and is shown to be, potentially, the Messiah. Joseph, our point of interest, is presented as responding most attentively to the Word of God as stated in the Scriptures. Moreover, in his decision to stay faithful to Mary and her child, Joseph is portrayed for us in the Gospel of Luke as a man who cooperates courageously with God’s will, by discerning it in the events occurring around him, about which he has to make real-life decisions.

Joseph is a wonderful model for Christians as we live in the world. The Word of God spoken in the Scriptures guides us, but many times we have to apply that Word in everyday situations where we must see the reality around us, decide what God desires us to do and then act courageously, justly and with compassion. Joseph shows us how to be persons of the Word of God, whether it is written in books or in the face of God’s creation, unfolding in history.

Michele A. Connolly RSJ is a Scripture scholar who teaches New Testament Studies at the Catholic Institute of Sydney.

| year_of_st_joseph_reflection_feb_2021.pdf | |

| File Size: | 274 kb |

| File Type: | |

NEW!!!

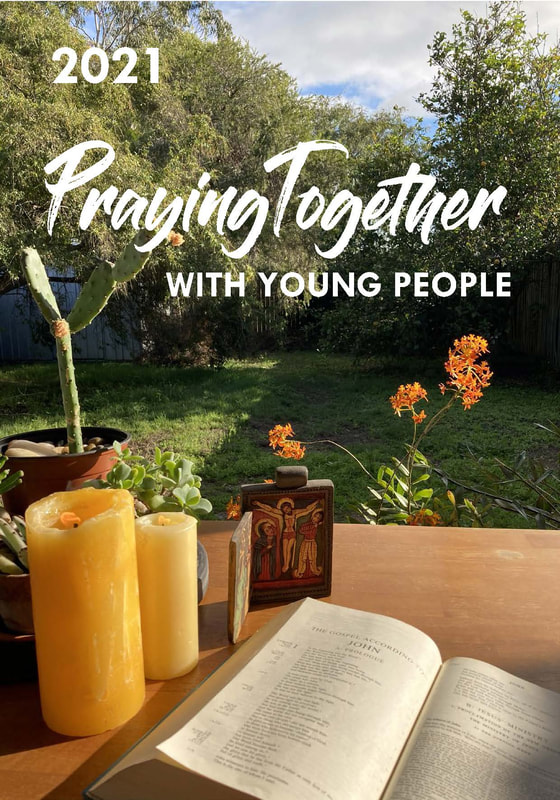

Praying Together With Young People 2021

Introducing a new daily prayer resource designed to help teachers, parents and catechists to lead prayer with a class or family. Also includes an electronic flip-book version of the book for easy display on screens.

The structure of the prayer for each weekday is the same so that prayer time becomes a familiar routine, leading children into a liturgical pattern of responses. Responses to the gospel reading for each day include intercessions, songs, guided meditations, short video clips or silent prayer. Hyperlinks in the electronic version of the resource provide easy access to online reflections.

Sample pages are available to view on the Liturgy Brisbane website. (Click on the image below)

Sunday Readings and Praying With Children resources are now available by subscription.

Resources are available to parishes, schools and to individual subscribers.

|

The Praying with Children resource has been expanded to include music (audio, sheet music and PowerPoint).

It also includes the features you have become familiar with, including a gospel reading, reflection, video, discussion topic and group activity. This resource has been designed for use: 1) at Children’s Liturgy of the Word during Sunday Mass and 2) by parents and children in the home. Subscribers receive an email each week which contains the link to the current week's web page, as well as an accompanying PDF. Parishes who subscribe may forward this email on to parishioners, or they may decide just to send the PDF. |

|

Liturgy News is undergoing a transformation in 2021. Previously a seasonal periodical available by subscription, Liturgy News will soon be freely available to all as a download from our website. Each issue features commentary and insight from Australia's leading liturgists and is written for parishes, schools, experts and novices. The complete index is searchable on the Liturgy Brisbane website, and all issues from 2001 onwards will soon be available as free PDF downloads. |

|

Now with new and improved features!

Subscribe now to gain access to this vital liturgy preparation resource. |

|

The Wedding by LITURGIA has been designed for couples who are preparing their wedding liturgy. This electronic resource contains all the readings and prayers from the new revised Order of Celebrating Matrimony as well as music suggestions and lyrics of hymns. It runs on all Internet enabled devices: PCs, Macs, Tablets and Phones. Choose from the full range of prayers and readings and prepare the liturgy from start to finish. No need to type in any texts! View music suggestions for each part of the liturgy and insert your chosen hymns, with lyrics, into your liturgy plan. Type in the names of the bride and groom, and the names appear correctly throughout all of the ritual texts. Export your liturgy to Word or PDF and print a booklet, or create a PowerPoint presentation for use on display screens. It also comes with a companion hard-copy book (pictured) which contains all the prayers and texts of the Catholic marriage rite along with other helpful information. Click here to order. |

|

The Funeral by LITURGIA is an electronic resource which has been designed for families who are preparing the funeral of a loved one, or for those who may wish to prepare their own funeral.

This electronic resource contains all the readings and prayers from the Order of Christian Funerals as well as music suggestions and lyrics of hymns. It runs on all Internet enabled devices: PCs, Macs, Tablets and Phones. Choose from the full range of prayers and readings and prepare the liturgy from start to finish with no need to type in any texts! Type in the name of the deceased and this name appears correctly throughout all of the ritual texts. Export your liturgy to Word or PDF and print a booklet, or create a PowerPoint presentation for use on display screens. This resource also comes with a companion hard-copy book (pictured) which contains all the prayers and texts of the Catholic funeral rite along with other helpful information. Click here to order |

Contact Us |

Images used under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0. Full terms at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0.

Other images from Unsplash.com and Pixabay.com. Used under license. Full terms and conditions.

Other images from Unsplash.com and Pixabay.com. Used under license. Full terms and conditions.