The centrality of the Eucharist: idea and performance

By Thomas O'Loughlin

‘The celebration of the Eucharist is the true centre of the whole Christian life both for the universal Church and for the local congregation of that Church.’ Those words from Eucharisticum Mysterium 1A of 1967 are the most lapidary form of an idea that was at the heart of the movement for liturgical renewal for most of the twentieth century and which was expressed in many places in the documents of Vatican II and texts that followed it. It has now achieved the dubious distinction of being a theological tag – a phrase invoked time after time with little thinking on any occasion – trotted out by presiders time after time on the importance of ‘taking part in the Eucharist’ or of ‘going to Mass’ (two phrases, two different theologies, two different spiritualities). The tag takes many forms: ‘the Eucharist is the centre of the Church’ or ‘the Eucharist is the centre and summit of the Christian life’ or ‘the Eucharist is the centre of the Church’s life.’ There cannot be a Catholic alive who has not heard it, and heard it again. And as with all such tags it contains a great truth and one that would not have been readily appreciated by many western Christians for more than a millennium. When it did start to appear in the second decade of the twentieth century it seems so revolutionary an idea – a focus on the Eucharist as an action as distinct from the Reformation / Tridentine interest in the twin ideas of ‘sacrifice’ and ‘sacrament’ – that every time it was used there was a need to spell out what was meant by ‘the Eucharist is central’ and to justify and defend it as a ‘new’ idea worth pursuing.

Now, half a century after the Council, the phrase trips off almost every tongue as if its meaning was as plain as black paint on a white wall. But like many such tags – used because they ‘sound right’ but with little thought – I suspect that, more often than not, it means very little to those who say it and it is no more than pious jargon to those who hear it.

Centres

The word ‘centre’ is so commonplace – we talk about ‘the city centre,’ ‘the parish centre’ [i.e. a hall], ‘cost-centres’ and ‘the centre of the circle’ – that we forget it has a very special meaning in religious discourse and especially when that has to do with human ritual. Mircea Eliade has shown, in a string of books, that the desire to find oneself ‘at the centre’ is a basic idea in all religious activity – for example it is a basic idea in pilgrimage. And Christian liturgists in the early twentieth century noted how liturgy was an important means by which the Church discerned what is at the core of its beliefs. Both these ideas about ‘the centre’ have influenced the Council.

But speaking of the centre of the Church’s life is also new in another way. If you asked a scholastic theologian in 1950 which were the central elements of Catholic doctrine / practice and which were peripheral, he would have been stumped. One could not arrange theology in terms of centre / periphery because that would presuppose what we now call a ‘hierarchy of truths’. In the 1950s, there was the simple binary of true / false, and one treated all the true ideas as so many bricks that could be assembled anyhow into an edifice. The Council saw that this approach not only failed to adequately proclaim the kerygma, but failed to answer the pressing questions of people about their faith, and, indeed, crazy theological jumbles where every bit was true but the resulting edifice was bizarre. To speak about the activity of Eucharist at the centre is to give it a unique place in Christian practice, and then to suggest that other realities have to be seen as off-shoots not as being entitled to ‘equal billing’ with it.

‘The celebration of the Eucharist is the true centre of the whole Christian life both for the universal Church and for the local congregation of that Church.’ Those words from Eucharisticum Mysterium 1A of 1967 are the most lapidary form of an idea that was at the heart of the movement for liturgical renewal for most of the twentieth century and which was expressed in many places in the documents of Vatican II and texts that followed it. It has now achieved the dubious distinction of being a theological tag – a phrase invoked time after time with little thinking on any occasion – trotted out by presiders time after time on the importance of ‘taking part in the Eucharist’ or of ‘going to Mass’ (two phrases, two different theologies, two different spiritualities). The tag takes many forms: ‘the Eucharist is the centre of the Church’ or ‘the Eucharist is the centre and summit of the Christian life’ or ‘the Eucharist is the centre of the Church’s life.’ There cannot be a Catholic alive who has not heard it, and heard it again. And as with all such tags it contains a great truth and one that would not have been readily appreciated by many western Christians for more than a millennium. When it did start to appear in the second decade of the twentieth century it seems so revolutionary an idea – a focus on the Eucharist as an action as distinct from the Reformation / Tridentine interest in the twin ideas of ‘sacrifice’ and ‘sacrament’ – that every time it was used there was a need to spell out what was meant by ‘the Eucharist is central’ and to justify and defend it as a ‘new’ idea worth pursuing.

Now, half a century after the Council, the phrase trips off almost every tongue as if its meaning was as plain as black paint on a white wall. But like many such tags – used because they ‘sound right’ but with little thought – I suspect that, more often than not, it means very little to those who say it and it is no more than pious jargon to those who hear it.

Centres

The word ‘centre’ is so commonplace – we talk about ‘the city centre,’ ‘the parish centre’ [i.e. a hall], ‘cost-centres’ and ‘the centre of the circle’ – that we forget it has a very special meaning in religious discourse and especially when that has to do with human ritual. Mircea Eliade has shown, in a string of books, that the desire to find oneself ‘at the centre’ is a basic idea in all religious activity – for example it is a basic idea in pilgrimage. And Christian liturgists in the early twentieth century noted how liturgy was an important means by which the Church discerned what is at the core of its beliefs. Both these ideas about ‘the centre’ have influenced the Council.

But speaking of the centre of the Church’s life is also new in another way. If you asked a scholastic theologian in 1950 which were the central elements of Catholic doctrine / practice and which were peripheral, he would have been stumped. One could not arrange theology in terms of centre / periphery because that would presuppose what we now call a ‘hierarchy of truths’. In the 1950s, there was the simple binary of true / false, and one treated all the true ideas as so many bricks that could be assembled anyhow into an edifice. The Council saw that this approach not only failed to adequately proclaim the kerygma, but failed to answer the pressing questions of people about their faith, and, indeed, crazy theological jumbles where every bit was true but the resulting edifice was bizarre. To speak about the activity of Eucharist at the centre is to give it a unique place in Christian practice, and then to suggest that other realities have to be seen as off-shoots not as being entitled to ‘equal billing’ with it.

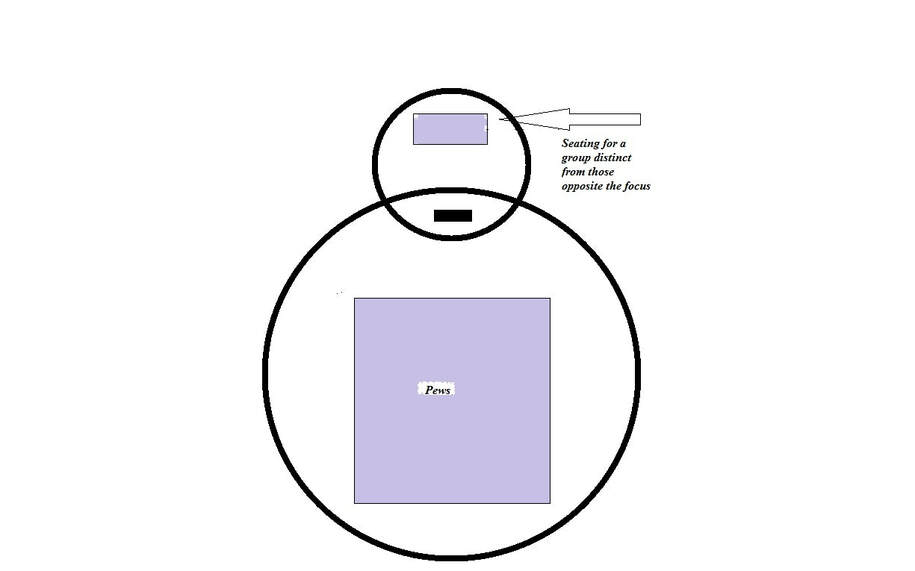

If ‘the Eucharist is the centre,’ then this understanding must take practical expression. It must be experienced where we celebrate. This chapel says to everyone who enters it: what happens around this table is central to this community. The hierarchy of truths is also visible: the place of reservation is honoured, but does not compete with the centrality of the whole community’s activity of joining with the Christ in praising the Father.

However, what was most revolutionary about the statement was that it placed the Eucharist not at the centre of the presbyter’s life (as many spiritual writers for more than a century had done), nor, indeed, at the centre of the life of the priest with his congregation, but at the centre of the life of the whole Church and each local church. We, the whole people gathered, have the Eucharist as our centre – and so the mediating role of the cleric (taken for granted before the Council but still very much alive) has simply disappeared.

‘Centre’ versus ‘Focus’

One feature of ‘a centre’ is that is presupposes a community. Something can only be central to both myself and another; indeed, to a whole group. It is the common reality that we hold. It is what we revolve around. Centrality is an ecclesial expression. In contrast to a centre is where I am interested in something, and I focus on it, and you too are equally interested in it and also focus on it. This latter shared interest we can describe as ‘focus.’ As with a centre a focus can be shared by a very large group, it may even generate a club fostering this focus, but it is less than a centre. I am a member of club that focuses on maps and mapping. It is the passion for me and for everyone else in the society and we have a journal, meetings, and lots of shared activities. But this common focus, for all its fun and value, is not the same as that which keeps a relationship or a family together. A centre is something that is dear to one’s heart precisely because it keeps us together and makes me and another (or others) into a genuine ‘us’. The Eucharist is not just a common focus, for a group of individuals who are just sharing a desire to get something (though this attitude was one of the besetting problems of the pre-1970 rite); the Eucharist is an activity that is central to us such that by engaging in it we are transformed into the People of God, the Body of Christ.

Centrality is an ‘I – Thou’ reality; focus is an ‘I – it’ event.

One of the great weaknesses of the medieval understanding was that the Mass was the focus of the priest, and then ‘getting communion’ was the focus of the laity – and, indeed, for most people most of the time it was simply worshipping the Blessed Sacrament and ‘hearing Mass’ that was the focus of ordinary people.

This understanding – where there was not even a shared focus between clergy and laity – was well expressed in older buildings. Indeed it can still be seen in many ‘re-ordered’ buildings where there is no centre but only a shared focus.

‘Centre’ versus ‘Focus’

One feature of ‘a centre’ is that is presupposes a community. Something can only be central to both myself and another; indeed, to a whole group. It is the common reality that we hold. It is what we revolve around. Centrality is an ecclesial expression. In contrast to a centre is where I am interested in something, and I focus on it, and you too are equally interested in it and also focus on it. This latter shared interest we can describe as ‘focus.’ As with a centre a focus can be shared by a very large group, it may even generate a club fostering this focus, but it is less than a centre. I am a member of club that focuses on maps and mapping. It is the passion for me and for everyone else in the society and we have a journal, meetings, and lots of shared activities. But this common focus, for all its fun and value, is not the same as that which keeps a relationship or a family together. A centre is something that is dear to one’s heart precisely because it keeps us together and makes me and another (or others) into a genuine ‘us’. The Eucharist is not just a common focus, for a group of individuals who are just sharing a desire to get something (though this attitude was one of the besetting problems of the pre-1970 rite); the Eucharist is an activity that is central to us such that by engaging in it we are transformed into the People of God, the Body of Christ.

Centrality is an ‘I – Thou’ reality; focus is an ‘I – it’ event.

One of the great weaknesses of the medieval understanding was that the Mass was the focus of the priest, and then ‘getting communion’ was the focus of the laity – and, indeed, for most people most of the time it was simply worshipping the Blessed Sacrament and ‘hearing Mass’ that was the focus of ordinary people.

This understanding – where there was not even a shared focus between clergy and laity – was well expressed in older buildings. Indeed it can still be seen in many ‘re-ordered’ buildings where there is no centre but only a shared focus.

This is a re-ordered ‘sanctuary’. The table is not the centre of the community but firmly in the area of the clergy: at best it is the intersection of a shared focus. This re-ordering shows a lack of theological understanding of the Eucharist as the centre of the Church combined with a failure of liturgical imagination. One cannot experience as sacred space the centrality of the Eucharist here.

We need as a Church to reflect on this difference between a common ‘centre’ and a shared ‘focus.’ Only by recognising the difference can we appreciate what we proclaim about the Eucharist. Too often this is how we think about the space.

This is not a case of us having as the whole church a common centre but two groups who simply interact. This is the theology of the church as the society of two unequal parts: the governors and the governed, the doers and the receivers, the clergy and the laity. Vatican II was a deliberate move to get away from this theology; but in too many buildings we have not got away from the experience.

A simple test

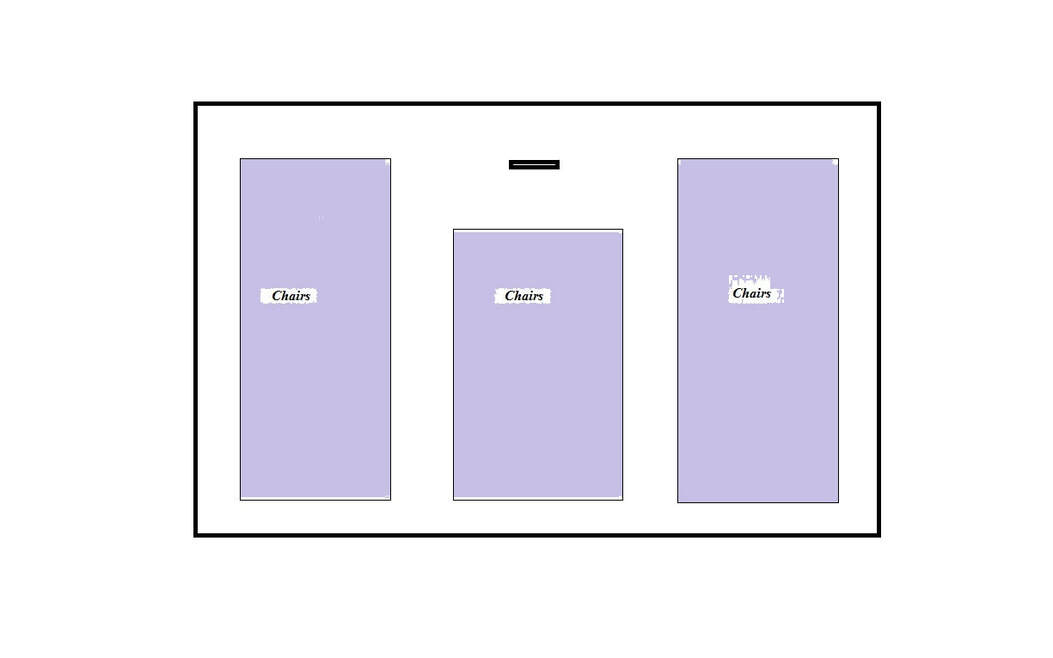

Recently I watched a group of people get ready to celebrate the Eucharist in a hall. The hall was completely clear when they arrived with the chairs stacked at one end along with a stack of about a dozen tables. How did they arrange the space? Would they use the chairs? If so, how would they arrange them? These were the questions in my head as I watched the preparations. This is what they came up with:

A simple test

Recently I watched a group of people get ready to celebrate the Eucharist in a hall. The hall was completely clear when they arrived with the chairs stacked at one end along with a stack of about a dozen tables. How did they arrange the space? Would they use the chairs? If so, how would they arrange them? These were the questions in my head as I watched the preparations. This is what they came up with:

This arrangement conveys at best ‘a matter of moment’ to all concerned. But it is two intersecting groups with a common focus.

This does not convey a centre.

This does not convey a centre.

They were so used to the shared focus notion, the experiential variant on ‘attending the Eucharist’ or ‘getting Mass’ that they did not think of this as a single shared event that was for them a centre.

Now look at this photograph and ask yourself what theology does it express?

Now look at this photograph and ask yourself what theology does it express?

We need to do a lot more thinking about space and environment if we want to take statements like ‘the Eucharist is the centre and summit of the Christian life’ seriously.

Further Reading

Richard Giles, Re-Pitching the Tent: Re-ordering the church building for worship and mission in the new millennium (Norwich 1996).

Richard Giles, Creating Uncommon Worship: Transforming the Liturgy of the Eucharist (Norwich 2004).

Thomas O’Loughlin, The Rites and Wrongs of Liturgy: Why Good Liturgy Matters (Collegeville, MN 2018).

Further Reading

Richard Giles, Re-Pitching the Tent: Re-ordering the church building for worship and mission in the new millennium (Norwich 1996).

Richard Giles, Creating Uncommon Worship: Transforming the Liturgy of the Eucharist (Norwich 2004).

Thomas O’Loughlin, The Rites and Wrongs of Liturgy: Why Good Liturgy Matters (Collegeville, MN 2018).