Sunday - The Original Feast

By Barry Craig

Why is Sunday our feast and rest day?

A simple sociological answer is that Christianity inherited, with a twist, the Jewish week and its seventh day of rest. We can see this in the later Christian revision of the translation of the Ten Commandments from keeping holy “the Sabbath Day” to “the Lord’s Day”.

A philosophical answer may see it as an expression of the intersecting of cosmology and human society, that is, the grand, transcendent and eternal scales within the small, immanent and ephemeral. As such it is a suitable vehicle for expressing our understanding of salvation history and its culmination in Christ.

All societies throughout history have paid attention to agricultural seasons determined by the solar cycle which describes the year. Ancient people also knew that the shifting patterns of the stars, with the exception of five wanderers, the visible planets, followed this solar cycle and could be used to calculate specific points in the year.

Why is Sunday our feast and rest day?

A simple sociological answer is that Christianity inherited, with a twist, the Jewish week and its seventh day of rest. We can see this in the later Christian revision of the translation of the Ten Commandments from keeping holy “the Sabbath Day” to “the Lord’s Day”.

A philosophical answer may see it as an expression of the intersecting of cosmology and human society, that is, the grand, transcendent and eternal scales within the small, immanent and ephemeral. As such it is a suitable vehicle for expressing our understanding of salvation history and its culmination in Christ.

All societies throughout history have paid attention to agricultural seasons determined by the solar cycle which describes the year. Ancient people also knew that the shifting patterns of the stars, with the exception of five wanderers, the visible planets, followed this solar cycle and could be used to calculate specific points in the year.

A shorter scale is needed to regulate our more complex social life and market days. The Moon provided it, from which we get our word month, so its cycle has been used from the dawn of time, especially using its four cardinal points of New and Full, together with the halves.

The Babylonians established rest days based on these four points, but these are not easy to determine and do fall slightly erratically seven to nine solar days apart. In fact, the easiest point to identify is the evening on which the crescent first appears after the New Moon; the first day of the month – and the ancient Latin practice of calling its sighting is the origin of our word Calendar. The Moon’s irregularities cause such difficulties that the systems based on it tend to disintegrate. Hence in Rome months became fixed at particular lengths irrespective of the Moon. They adopted an eight day week that began with the market day; in fact, this was considered a nine day cycle with the ninth of one being considered also the first of the next cycle. Thus in a sense the first and ninth days were the same. Apart from the market, many other activities were prohibited on this day.

The Babylonians established rest days based on these four points, but these are not easy to determine and do fall slightly erratically seven to nine solar days apart. In fact, the easiest point to identify is the evening on which the crescent first appears after the New Moon; the first day of the month – and the ancient Latin practice of calling its sighting is the origin of our word Calendar. The Moon’s irregularities cause such difficulties that the systems based on it tend to disintegrate. Hence in Rome months became fixed at particular lengths irrespective of the Moon. They adopted an eight day week that began with the market day; in fact, this was considered a nine day cycle with the ninth of one being considered also the first of the next cycle. Thus in a sense the first and ninth days were the same. Apart from the market, many other activities were prohibited on this day.

Babylon chose a seven day cycle with the last being the rest day. While in Babylonia the Hebrews adopted its seven day week, their penchant for punning reinforcing the association of seven (shebaʿ) and rest (shābat) and giving rise to their name for the seventh as Sabbath (Shabbāt). This was then enshrined by inclusion in the Scriptures which were being formulated at the time, in the process endowing the Babylonians seven days with a new meaning. God was poetically described as working for six days to make the cosmos and humankind, and as consecrating the seventh for rest; its observance became a holy duty and sine qua non of Jewish religious life.

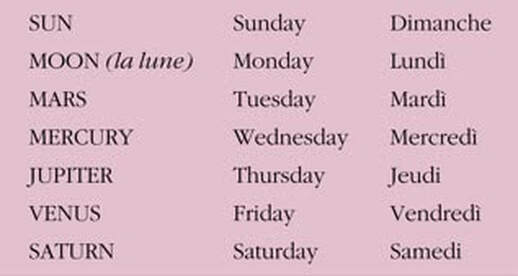

To the spreading Babylonian system was added the convention of naming the days after the seven celestial bodies that move independently of the stars, namely the Sun, Moon and five visible planets in the order of Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus and Saturn.

To the spreading Babylonian system was added the convention of naming the days after the seven celestial bodies that move independently of the stars, namely the Sun, Moon and five visible planets in the order of Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus and Saturn.

(The derivation of these names is clearer in the Romance languages than in the Germanic languages, as seen in the French names below, although Sunday derives from the Lord's Day rather than the Sun.)

The Babylonian system spread even to Rome and China but was used alongside local systems, but the Christian revision of its Jewish form became fully established in Rome and the Empire from Constantine’s edict on 3 March 321 that established Sunday as the official day of rest. Things formerly forbidden on market days, and the markets themselves, were now forbidden on Sunday.

|

SUNDAY

Why had Christians adopted Sunday as their day of worship rather than the Saturday inherited from the Jews? The answer is not as simple to determine as might be expected, for while we think of it as the celebration of the resurrection, it is entirely conceivable that the well-established Jewish worship on the Sabbath could have been kept. Indeed it appears that some ancient Christian communities did keep the Sabbath, especially those that were Jewish. Or it might have been possible to establish Thursday evening for the Eucharist in recollection of the Last Supper – as indeed we do annually on Holy Thursday. Or choosing Friday in honour of Christ’s saving death might have been possible. So why specifically Sunday, the day of the Resurrection? The difficulty for historians is that our early centuries are obscure, with only a few glimpses before clear information starts to emerge from the third century. The New Testament gives the earliest scant evidence of emergent Church activity on Sundays. Paul suggests a weekly contribution to help the faithful in Jerusalem (1 Cor 16:2) but this is ambiguous, perhaps referring to the first day of the week, or perhaps to one day each week without specifying which. Then each Gospel attentively specifies the resurrection as being on the first day of the week, and Acts 20:7 refers clearly to the disciples gathering on it for the breaking of bread (a Christian neologism for the Eucharist, not merely a meal). |

Another line of interest is found the two instances of kyriakos (Lord’s) a peculiar adjective not exactly equivalent to the noun form, tou kyriou (of the Lord). Rarely used in Classical Greek it gained new life in Christianity, beginning with Paul speaking of the Eucharist as Lord’s Supper (1 Cor 11:20). He did not say on which day this was held, nor even if it was associated with a particular day. The other is Revelation 1:10, placing John's vision on the Lord’s day, without making it clear which day of the week that was. It is possible that this neologism was coined in the Greek Jewish diaspora to refer to the Sabbath, but once the obscurity of the first centuries lifts it becomes clear that the Christian tradition unequivocally associates that name with Sunday. Eliding the noun it qualified, the adjective became a noun in ecclesiastical Greek (Kyriake) and Latin (Dominica) and this became the name of the day with the remaining weekdays referred to by number. A parallel usage of the adjective in the Lord’s house or household similarly becomes kyriakon, from which our word church derives.

In the mid-first century Justin Martyr uses the days’ celestial names since he is writing to pagans. Of particular interest is 1 Apology 67 where he not only testifies to Sunday as the day on which the church members assembled to worship, but he puts forward two reasons for its being so. Firstly, he says that, having changed darkness and matter, God made the world on this day. This changes the usual focus from the six days of Genesis as a whole to the critically important first day on which all the others depend. It could be that he was simply working with the school of thought held by many pagan philosophers that the world was indeed divinely created, even though their conception of it was not shaped by the Jewish creation story. Nonetheless, Justin witnesses to a view of creation that is not bound to the seven day week. Secondly, it is the day of the Lord’s resurrection, but this as a simple fact was not sufficient; he goes on to say that the practices he has been explaining, specifically Baptism and the Eucharist, were taught by Jesus on this day, the day of his resurrection. Indeed, while Paul associated the Eucharist with the Last Supper, and the three Synoptic gospels also appear to report it in that way, that connection was not universally held to be of prime importance until those texts shaped the anaphoras that emerged from the third century. Hence many primitive eucharistic texts do not mention the Last Supper at all and more often refer to the event of the resurrection, or at least to the fact of Christ risen. According to Justin, perhaps supported by glimpses in other ancient sources, the Eucharist (and also Baptism into the death and resurrection) was a post-resurrection teaching, and thus belonged to the new creation in Christ.

In the mid-first century Justin Martyr uses the days’ celestial names since he is writing to pagans. Of particular interest is 1 Apology 67 where he not only testifies to Sunday as the day on which the church members assembled to worship, but he puts forward two reasons for its being so. Firstly, he says that, having changed darkness and matter, God made the world on this day. This changes the usual focus from the six days of Genesis as a whole to the critically important first day on which all the others depend. It could be that he was simply working with the school of thought held by many pagan philosophers that the world was indeed divinely created, even though their conception of it was not shaped by the Jewish creation story. Nonetheless, Justin witnesses to a view of creation that is not bound to the seven day week. Secondly, it is the day of the Lord’s resurrection, but this as a simple fact was not sufficient; he goes on to say that the practices he has been explaining, specifically Baptism and the Eucharist, were taught by Jesus on this day, the day of his resurrection. Indeed, while Paul associated the Eucharist with the Last Supper, and the three Synoptic gospels also appear to report it in that way, that connection was not universally held to be of prime importance until those texts shaped the anaphoras that emerged from the third century. Hence many primitive eucharistic texts do not mention the Last Supper at all and more often refer to the event of the resurrection, or at least to the fact of Christ risen. According to Justin, perhaps supported by glimpses in other ancient sources, the Eucharist (and also Baptism into the death and resurrection) was a post-resurrection teaching, and thus belonged to the new creation in Christ.

Similarly to the Romans’ inclusive counting system that allowed them to refer to the markets in their eight-day week as being every ninth day (nundinae), the Christian association of the seven days of creation with the Christ’s resurrection on the first day generated a reference to it as the Eighth Day. This does not suggest a new day being added to the unfinished work of creation but rather the return to and completion of the first day. It is both the first day of creation and the first day of its restoration or salvation in the New Creation.

From this brief discussion, our Sunday is seen to be not merely a weekly recollection of a particular event or duty, as perhaps “pay day” and “laundry day” may have been for people. It is a metaphoric reference to God’s creative activity (even though we no longer envisage it literally unfolding in six days). Its observance embodies our recognition that we are creatures and that we are only rightly aligned with God and creation when we acknowledge and offer due worship to our creator. Meshed with this is the recognition of Christ Jesus as the creator in the flesh, in whose image we are made and in whose resurrection we are remade. Thus the Jewish observance of rest and worship on Saturdays as the sine qua non of their religious duty; it became for early Christians sine dominicum non possumus, or, without Sunday we cannot exist.

This article reprinted from Liturgy News Vol 47(1) 2017